Invictus

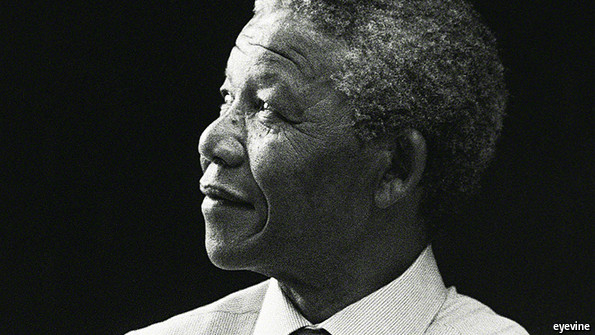

AMONG Nelson Mandela’s many achievements, two stand out. First, he was the world’s most inspiring example of fortitude, magnanimity and dignity in the face of oppression, serving more than 27 years in prison for his belief that all men and women are created equal. During the bleak years of his imprisonment on Robben Island, thanks to his own patience, humour and capacity for forgiveness, he seemed freer behind bars than the men who kept him there, locked up as they were in their own self-demeaning prejudices. Indeed, his warders were among those who came to admire him most.

Second, and little short of miraculous, was the way in which he engineered and oversaw South Africa’s transformation from a byword for nastiness and narrowness into, at least in intent, a rainbow nation in which people, no matter what their colour, were entitled to be treated with respect.

Exorcising the curse of colour

As a politician, and as a man, Mr Mandela had his contradictions (see article). He was neither a genius nor, as he often said himself, a saint. Some of his early writings, though infused with justifiable anger, were banal Marxist ramblings. But his charisma was evident from his youth. He was a born leader who feared nobody, debased himself before no one and never lost his sense of humour. He was handsome and comfortable in his own skin. In a country in which the myth of racial superiority was enshrined in law, he never doubted his right, and that of all his compatriots, to equal treatment.No less remarkably, once the majority of citizens were able to have their say he never denied the right of his white compatriots to equality. For all the humiliation he suffered at the hands of white racists before he was released in 1990, he was never animated by a desire for revenge. He was himself utterly without prejudice, which is why he became a symbol of tolerance and justice across the globe.

Perhaps even more important for the future of his country was his ability to think deeply, and to change his mind. When he was set free, many of his fellow members of the African National Congress (ANC) remained disciples of the dogma promoted by their party’s supporter, the Soviet Union, whose implosion shifted the global balance of power and thus contributed to apartheid’s demise. Many of his ANC comrades were members of the South African Communist Party who hoped to dismember the capitalist economy and bring its mines and factories into public ownership. Nor was the ANC convinced that a Westminster-style parliamentary democracy—with all the checks and balances of bourgeois institutions such as an independent judiciary—was worth preserving, perverted as it had been under apartheid.

Mr Mandela had himself harboured such doubts. But immediately before and after his release from prison, he sought out a variety of opinions from those who, unlike himself, had been fortunate enough to roam the world and compare competing systems. He listened and pondered—and decided that it would be better for all his people, especially the poor black majority, if South Africa’s existing economic model were drastically altered but not destroyed, and if a liberal democracy, with a universal franchise were established.

That South Africa did, in the end, move with relatively little bloodshed to become a multiracial free-market democracy was indeed a near-miracle for which the whole world must thank him. The country he leaves behind is a far better custodian of human dignity than the one whose first democratically elected president he became in 1994. A self-confident black middle class is emerging. Democracy is well-entrenched, with regular elections, a vibrant press, generally decent courts and strong institutions. And South Africa still has sub-Saharan Africa’s biggest and most sophisticated economy.

But since Mr Mandela left the presidency in 1999 his beloved country has disappointed under two flawed leaders, Thabo Mbeki and now Jacob Zuma. While the rest of Africa’s economy has perked up, South Africa’s has stumbled. Nigeria’s swelling GDP is closing in on South Africa’s. Corruption and patronage within the ANC have become increasingly flagrant. An authoritarian and populist tendency in ruling circles has become more strident. The racial animosity that Mr Mandela so abhorred is infecting public discourse. The gap between rich and poor has remained stubbornly wide. Barely two-fifths of working-age people have jobs. Only 70% of those who take the basic high-school graduation exam pass it. Shockingly for a country so rich in resources, nearly a third of its people still live on less than $2 a day.

Without the protection of Mr Mandela’s saintly aura, the ANC will be more harshly judged. Thanks to its corruption and inefficiency, it already faces competition in some parts of the country from the white-led Democratic Alliance. South Africa would gain if the ANC split, so there were two big black-led parties, one composed of communists and union leaders, the other more liberal and market-friendly.

Man of Africa, hero of the world

The ANC’s failings are not Mr Mandela’s fault. Perhaps he could have been more vociferous in speaking out against Mr Mbeki’s lethal misguidedness on the subject of HIV/AIDS, which cost thousands of lives. Perhaps he should have spoken up more robustly against the corruption around Mr Zuma. In foreign affairs he was too loyal to past friends, such as Fidel Castro. He should have been franker in condemning Robert Mugabe for his ruination of Zimbabwe.But such shortcomings—and South Africa’s failings since his retirement from active politics—pale into insignificance when set against the magnitude of his overall achievement. It is hard to think of anyone else in the world in recent times with whom every single person, in every corner of the Earth, can somehow identify. He was, quite simply, a wonderful man.

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario