A visual history of human sensemaking, from cave paintings to the world wide web.

Since the dawn of recorded history, we’ve been using visual depictions to map the Earth, order the heavens, make sense of time, dissect the human body, organize the natural world, perform music, and even concretize abstract concepts like consciousness and love. 100 Diagrams That Changed the World (UK; public library) by investigative journalist and documentarian Scott Christianson

chronicles the history of our evolving understanding of the world

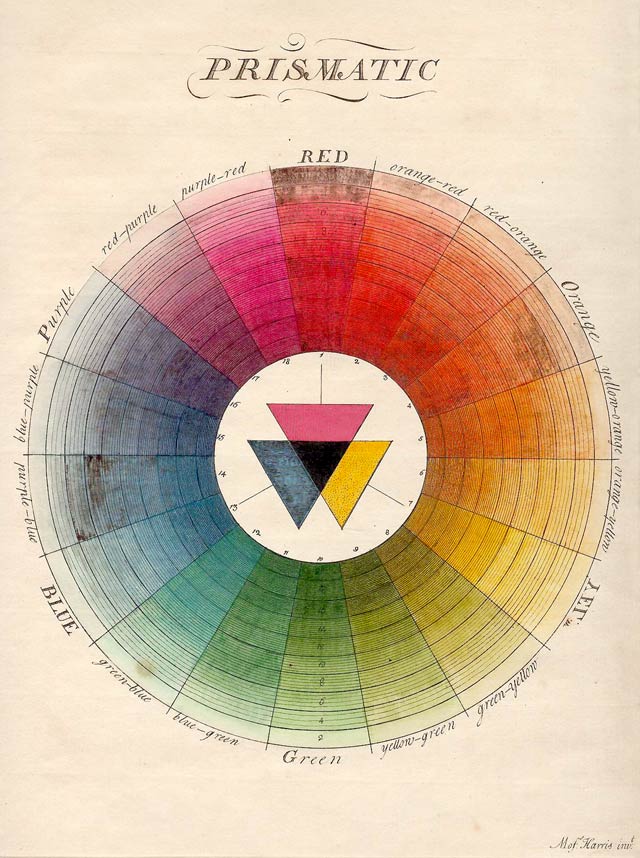

through humanity’s most groundbreaking sketches, illustrations, and

drawings, ranging from cave paintings to The Rosetta Stone to Moses

Harris’s color wheel to Tim Berners-Lee’s flowchart for a “mesh”

information management system, the original blueprint for the world wide

web.

Since the dawn of recorded history, we’ve been using visual depictions to map the Earth, order the heavens, make sense of time, dissect the human body, organize the natural world, perform music, and even concretize abstract concepts like consciousness and love. 100 Diagrams That Changed the World (UK; public library) by investigative journalist and documentarian Scott Christianson

chronicles the history of our evolving understanding of the world

through humanity’s most groundbreaking sketches, illustrations, and

drawings, ranging from cave paintings to The Rosetta Stone to Moses

Harris’s color wheel to Tim Berners-Lee’s flowchart for a “mesh”

information management system, the original blueprint for the world wide

web.But most noteworthy of all is the way in which these diagrams bespeak an essential part of culture — the awareness that everything builds on what came before, that creativity is combinatorial, and that the most radical innovations harness the cross-pollination of disciplines. Christianson writes in the introduction:

It appears that no great diagram is solely authored by its creator. Most of those described here were the culmination of centuries of accumulated knowledge. Most arose from collaboration (and oftentimes in competition) with others. Each was a product and a reflection of its unique cultural, historical and political environment. Each represented specific preoccupations, interests, and stake holders.

[…]

The great diagrams depicted in the book form the basis for many fields — art, astronomy, cartography, chemistry, mathematics, engineering, history, communications, particle physics, and space travel among others. More often than not, however, their creators — mostly known, but many lost to time — were polymaths who are creating new technologies or breakthroughs by drawing from a potent combination of disciplines. By applying trigonometric methods to the heavens, or by harnessing the movement of the sun and the planets to keep time, they were forging powerful new tools; their diagrams were imbued with synergy.

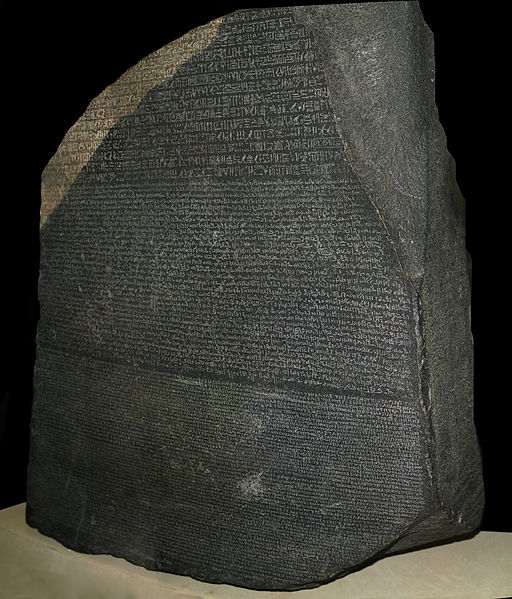

Discovered in 1799, this granite block containing a decree written in three languages allowed Egyptologists to interpret hieroglyphics for the first time -- a language that had been out of use since the fourth century AD.

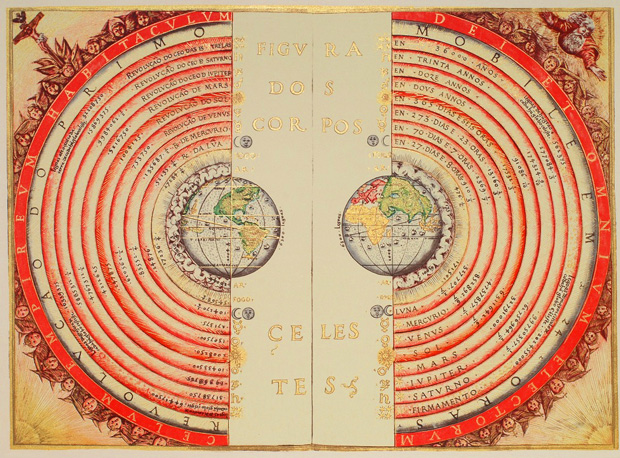

This 1568 illuminated illustration of the Ptolemaic geocentric system, 'Figura dos Corpos Celestes' (Four Heavenly Bodies), is by the Portuguese cosmographer and cartographer Bartolomeu Velbo.

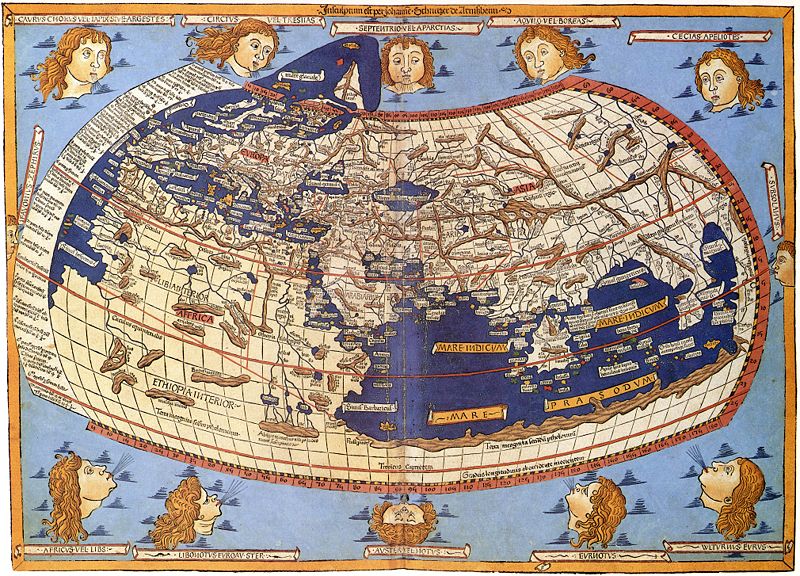

In this 15th-century example of the Ptolemaic world map, the Indian Ocean is enclosed and there is no sea route around the Cape. The 'inhabited' (Old) World is massively inflated.

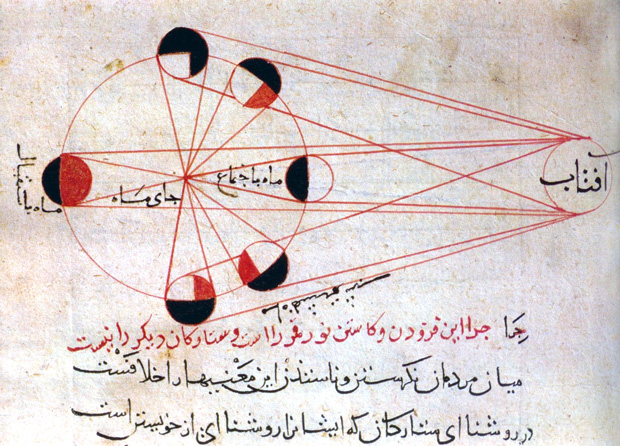

An illustration showing the different phases of the moon from al-Biruni's manuscript copy of his Kitab al-Tafhim (Book of Instruction on the Principles of the Art of Astrology)

diagram

From the latin diagramma (figure) from Greek, a figure worked out b lines, plan, from diagraphein, from graphein to write.

First known use of the word: 1619.

- A plan, a sketch, drawing, outline, not necessarily representational, designed to demonstrate or explain something or clarify the relationship existing between the parts of the whole.

- In mathematics, a graphic representation of an algebraic or geometric relationship. A chart or graph.

- A drawing or plan that outlines and explains the parts, operation, etc. of something: a diagram of an engine.

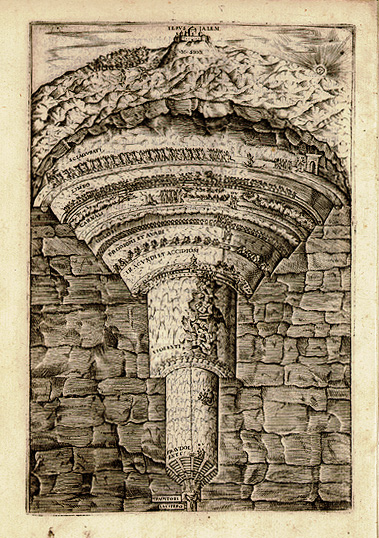

A 19th-century interpretation of Dante's map of Hell. The level of suffering and wickedness increases on the downward journey through the inferno's nine layers. No original copies of Dante's manuscript survive.

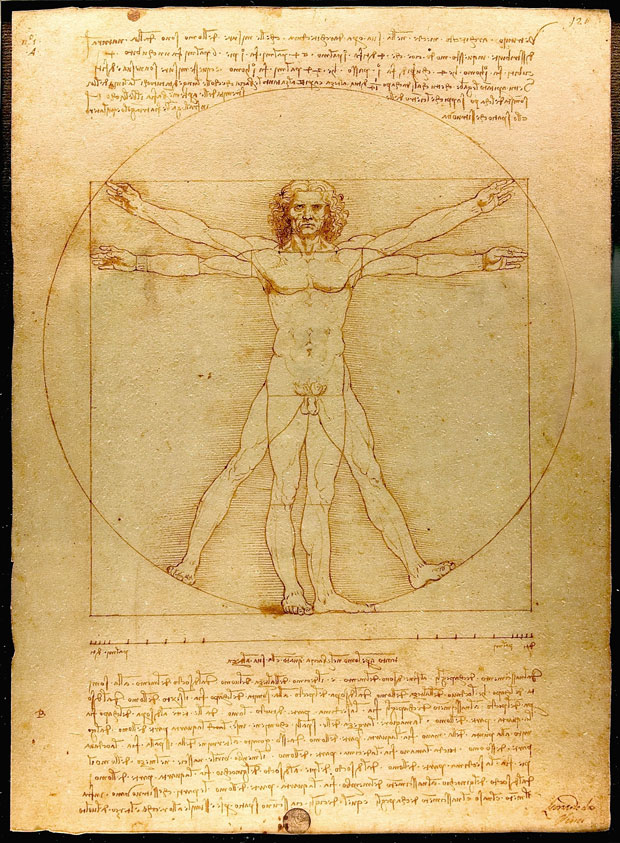

This sketch, and the notes that go with it, show how da Vinci understood the proportions of the human body. The head measured from the forehead to the chin was exactly one tenth of the total height, and the outstretched arms were always as wide as the body was tall.

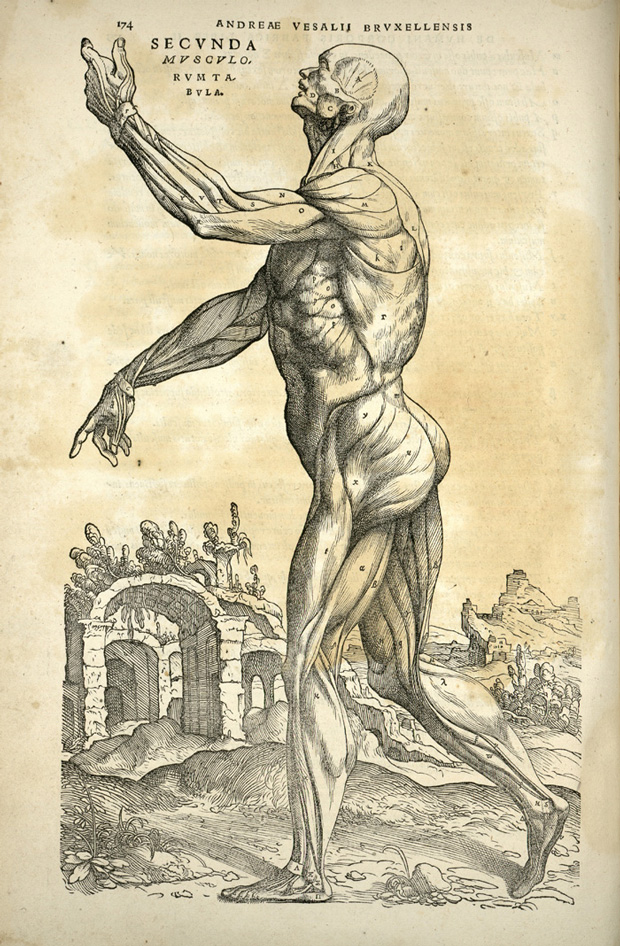

Vesalius's revolutionary anatomical treatise, De Humani Corporis Fabrica, shows the dissected body in unusually animated poses. These detailed diagrams are perhaps the most famous illustrations in all of medical history.

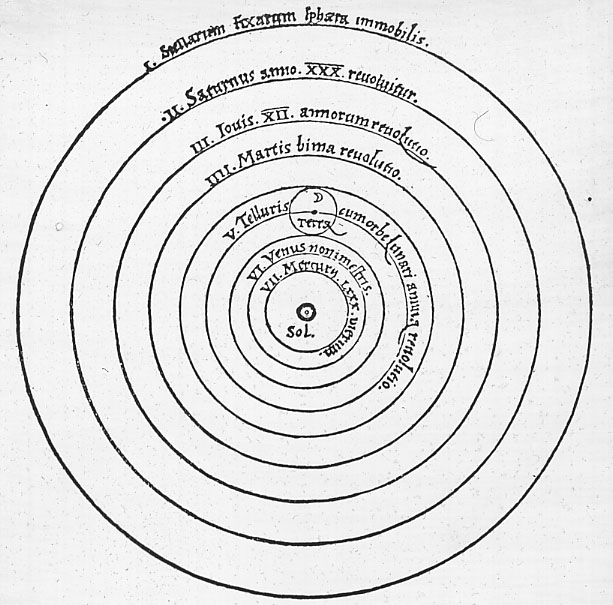

Copernicus's revolutionary view of the universe was crystallized in this simple yet disconcerting line drawing. His heliocentric model -- which placed the Sun and not the Earth and the center of the universe -- contradicted 14th-century beliefs.

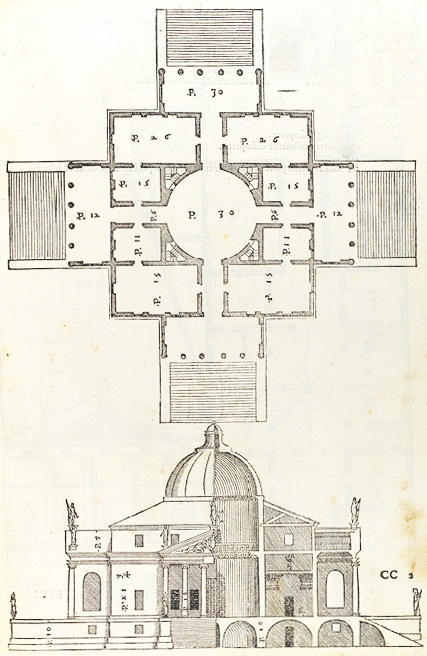

Palladio's country villas, urban palazzos, and churches combined modern features with classical Roman principles. His designs were hailed as 'the quintessence of High Renaissance calm and harmony.'

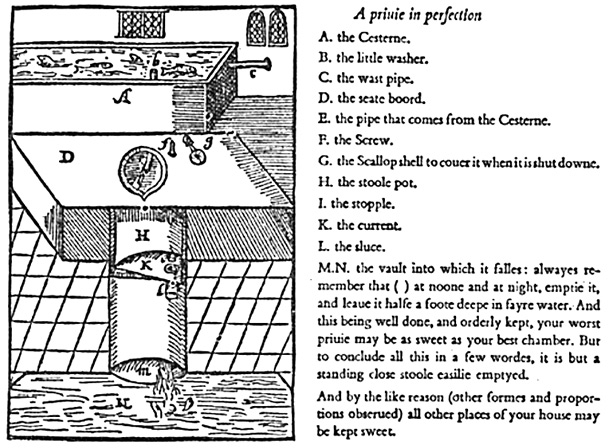

The text accompanying Harington's diagram identified A as the 'Cesterne,' D as the 'seate boord,' H as the 'stoole pot,' and L as the 'sluce.' If used correctly, 'your worst privie may be as sweet as your best chamber.'

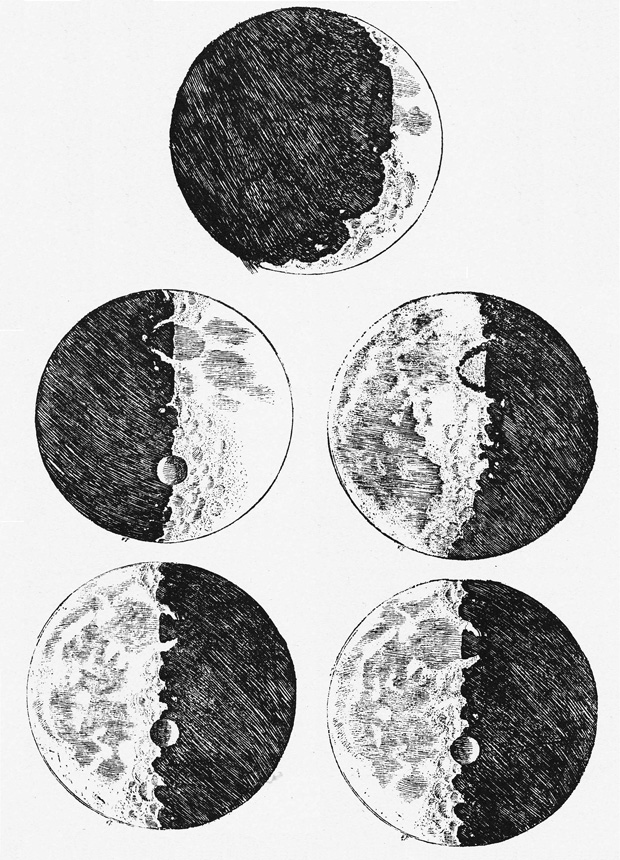

Aided by his telescope, Galileo's drawings of the moon were a revelation. Until these illustrations were published, the moon was thought to be perfectly smooth and round. Galileo's sketches revealed it to be mountainous and pitted with craters.

Moses Harris's chart was the first full-color circle. The 18 colors of his wheel were derived from what he then called the three 'primitive' colors: red, yellow and blue. At the center of the wheel, Harris showed that black is formed by the superimposition of these colors.

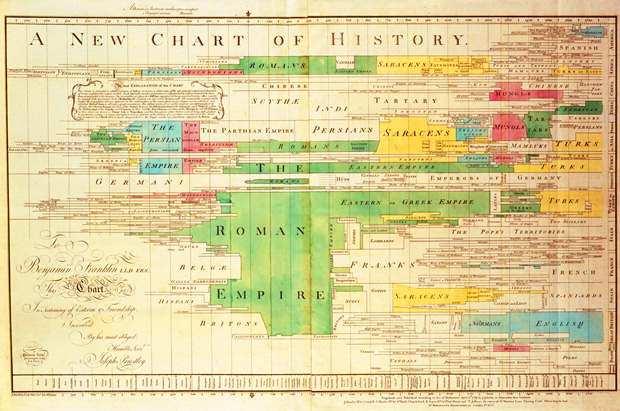

The regularized distribution of dates on Priestley's chart and its horizontal composition help to emphasize the continuous flow of time. This innovative, colorful timeline allowed students to survey the fates of 78 kingdoms in one chart.

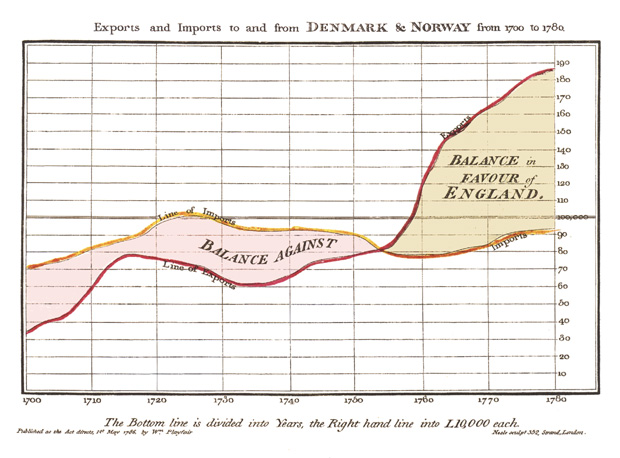

William Playfair was the first person to display demographic and economic data in graph form. His clearly drawn, color-coded line graphs show time on the horizontal axis and economic data or quantities on the vertical axis.

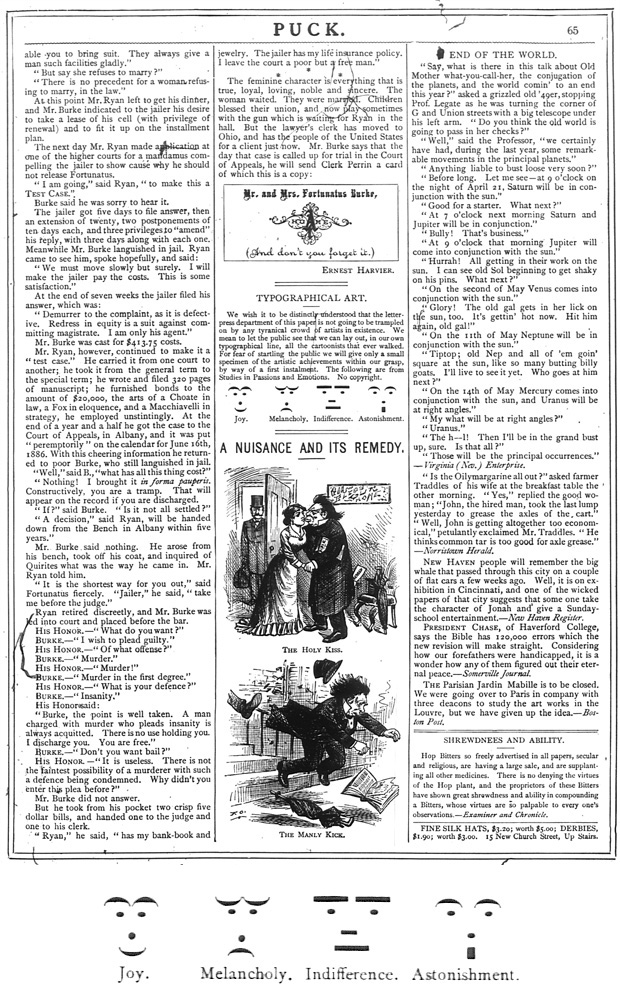

Emoticons made a discreet entrance, arriving in print for the first time in this March 30, 1881 issue of Puck. The small item in the middle of this page gives four examples of 'typographical art' -- joy, melancholy, indifference, and astonishment.

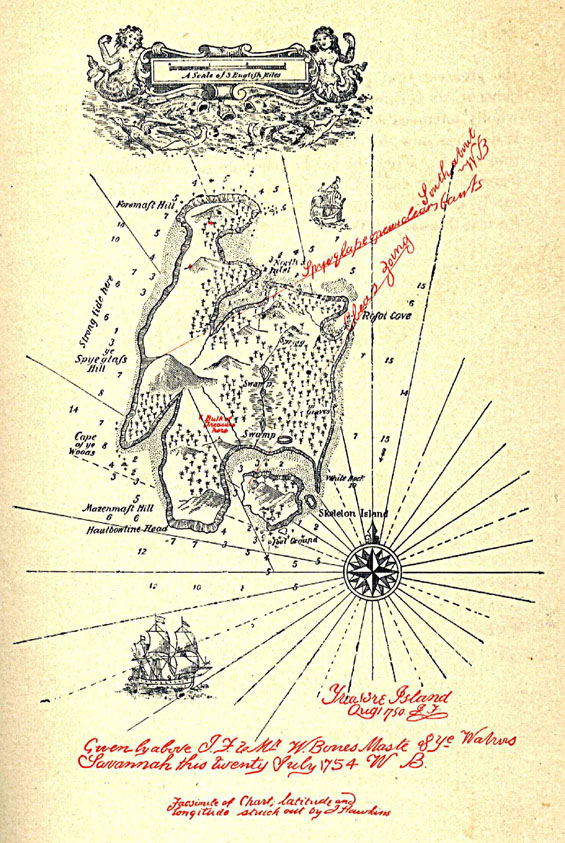

While there is no evidence of real pirates ever leaving a 'treasure map' showing where they had buried their stolen goods, with 'X' marking the spot, Stevenson's fictional device has continued to excite generations of children to this day.

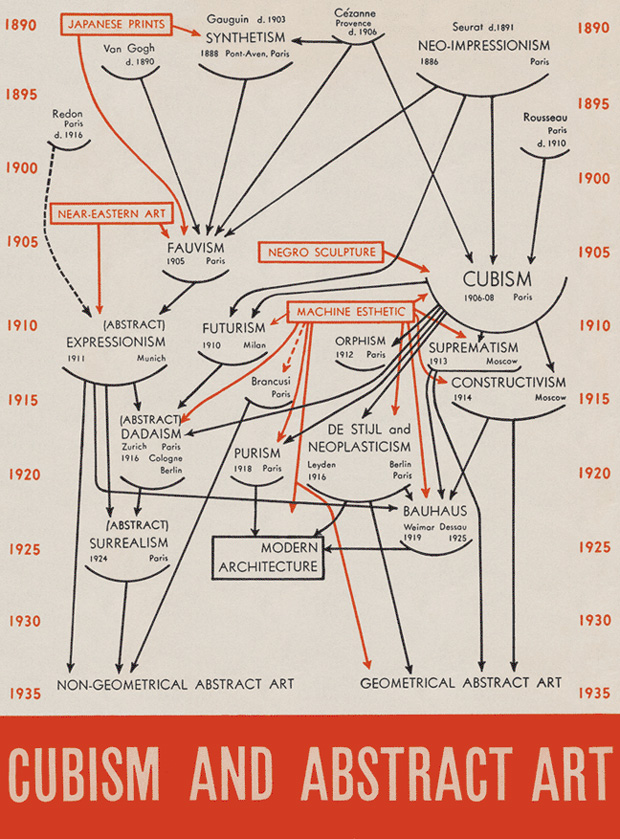

Barr's striking diagram highlighted the role that cubism had played in the development of modernism. Like the exhibition and book that accompanied it, Barr's diagram was a watershed in the history of 20th-century modernism.

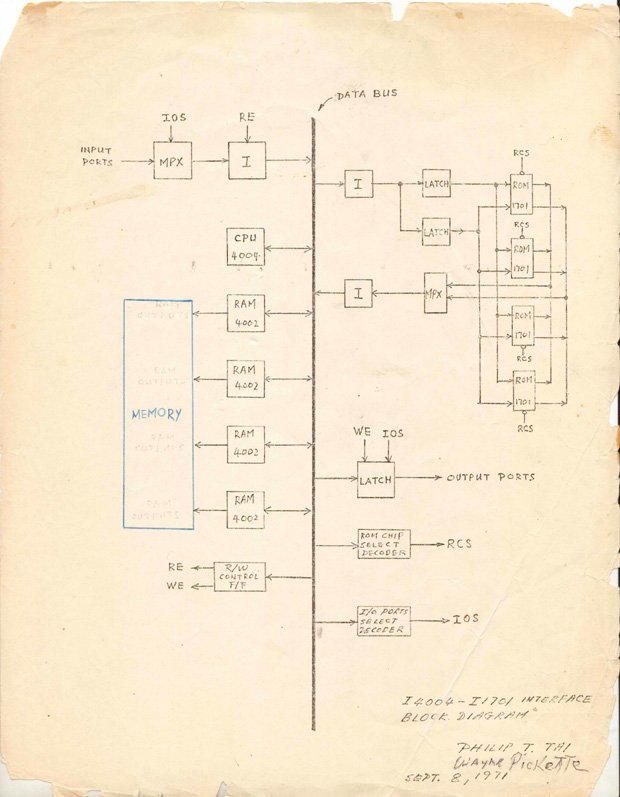

Wayne Pickette suggested that Intel could use a 'computer on a board' for one of their projects with the Japanese company Busicom. Pickette drew this diagram with Philip Tai for the 4004 demonstration board.

Thanks, Kirstin

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario